Is Tuition-Free Medical School for All the Best Use of Resources to Address Shortage of Primary…

Is Tuition-Free Medical School for All the Best Use of Resources to Address Shortage of Primary Care Physicians and the Lack of Socioeconomic Diversity in Medical School?

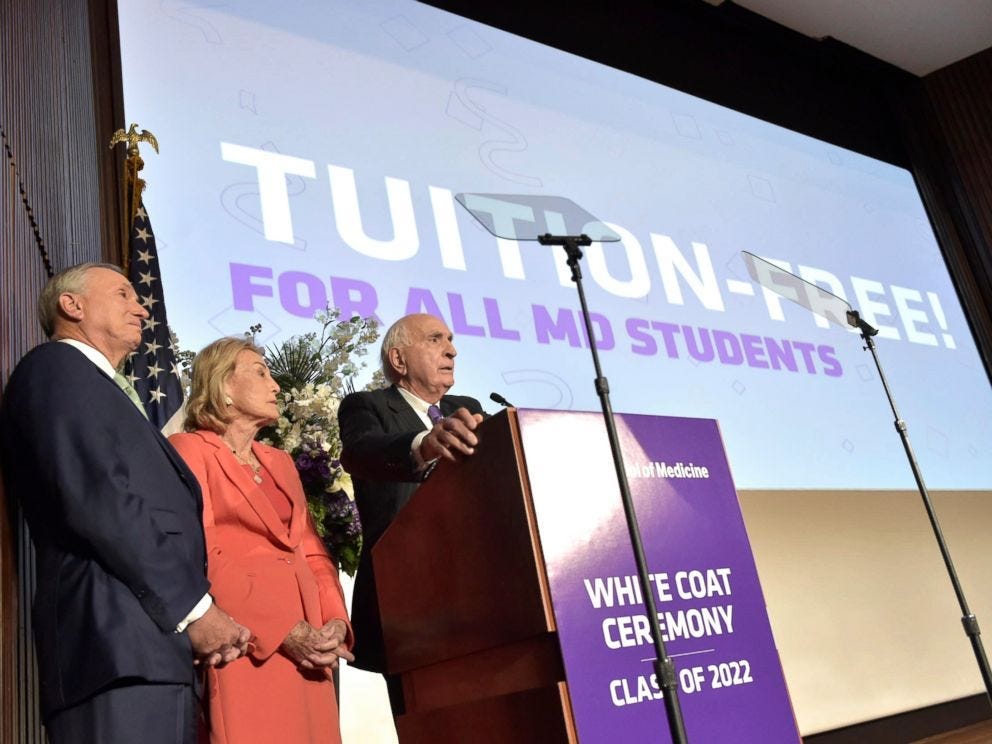

“Why didn’t I apply to NYU?” is the first thought that went through my mind when New York University School of Medicine announced last week that it will make medical school tuition-free for all incoming and returning students. I was excited for my peers 2 hours south on interstate 95. Addressing the debt burden for medical trainees is important, as medical school has gotten more and more expensive over the last decades. After giving it further thought, I think, however, that the funds could be allocated in a more thoughtful manner given the medical school’s intent: to increase the number of students going into primary care, and to increase socioeconomic diversity among the medical school’s student body.

“NYU also says medical school debt is ‘reshaping the medical profession,’ as graduates choose more lucrative specialized fields in medicine rather than primary care […] The school says it hopes the plan will also increase diversity among its students — what it calls ‘a full retrofitting of the pipeline that trains and finances’ future doctors.” James Doubek, NPR.

America is facing a looming shortage of primary care physicians: the estimated shortage will be between 8,700 and 43,100 physicians nationally by 2030 according to a recent report by the AAMC. Reports attribute medical students’ gravitating towards specialties to higher pay. Specialists earn on average $316,000, while primary care physicians earn on average $217,000. This near additional $100,000 yearly, is preferred, reports would say, because of the amount of debt students incur while in medical school. A recent report published in JAMA suggests however, that debt is likely to be less of a determinant of specialty choice than is future income. We do of course, function in a healthcare system that undervalues primary care. This has been palpable at my medical school. Research, is highly prioritized, and specialties are emphasized early on. There is a dearth of mentors for students interested in primary care. At the time of residency applications, students interested in family medicine must be advised by a faculty-person based out of a neighboring medical school… because we do not have a family medicine department. Neither does NYU.

Medical schools that prioritize training primary care physicians for the communities in which they are located make it clear at every stage of their medical education process. They state it in their mission statements, and emphasize it during the 4 years of training. Morehouse School of Medicine for example, was created with the specific goal of increasing the number of primary care physicians in Georgia. Morehouse placed first in the medical school social mission ranking, a tool used to measure and compare schools’ social impact, based on the number of graduates who practice primary care, work in health professional shortage areas, and are underrepresented minorities. NYU conversely, landed the 5th lowest in the same ranking. These schools attract, and select different types of students, in large part because of what their mission is vis-à-vis society. Prestigious schools are likely to select for students who perform extremely well on standardized tests and have robust research experience, whereas more socially oriented schools select for students who, besides meeting the qualifications for admission, may also grapple with inequality. That is not to say that all students who perform well on standardized tests do not grapple with inequality, but facing inequalities certainly impacts students’ ability to do so.

I’d argue that the financial incentive for students interested in primary care should be disbursed in the form of a loan forgiveness program, requiring that the beneficiaries commit a certain number of years to practicing primary care, akin to the national health service corps loan repayment program. A similar model has been adopted by several institutions of higher learning, where graduates who go into public interest or non-profit work instead of high paying jobs receive a sliding-scale rebate on their business or law school loans.

Furthermore, most medical students come from the top two quintiles of family income. This majority can afford the resources required to prepare for and eventually get into medical schools. Making medical school tuition-free for all as a way to help students from a lower socioeconomic status should go hand in hand with committing to breaking down barriers that keep those students from entering medical schools. All other things being equal, this policy would otherwise mostly make NYU more attractive to the same pool of applicants that face the tough choice of picking which prestigious medical school to attend. In fact, when asked in a previous interview about financial aid initiatives aimed at students from marginalized backgrounds, Yale School of Medicine’s dean Dr. Robert Alpern said:

“We all offer scholarships to steal students from other schools, to save our own skin, but in fact we don’t do anything for the country. All we do is shuffle these students around. A more comprehensive solution would be beyond the university’s capacity.”

Now having raised nearly half a billion dollars, NYU does have a certain capacity to contribute to more comprehensive efforts. It may be more socially impactful to broaden the pool of applicants by taking into even greater consideration factors outside of test scores and elements tied to privilege, and by making significant financial contributions to sustainable pipeline efforts and additional support for current underprivileged medical trainees. Aforementioned Morehouse is a leader in this realm, having invested in 9 K-12, 6 undergraduate and 2 post-baccalaureate pipeline programs.

To be sure, the debt burden for the average medical graduate is exorbitant, and medical schools along with policy makers should put forth efforts to make medical education more accessible and affordable, compromising perhaps on need-base policies. Take a completely different system, France: like the rest of higher education, medical school is free for all, and the cost burden is carried by the government. In exchange, the government works with physician unions to ensure that the cost of healthcare remains affordable, which in part makes medicine less lucrative than it is in the U.S. Additionally, the income gap between specialists and general practitioners is noticeably smaller: in 2016 the median income for generalists/primary care providers was 79,600€, and for specialists, it was 80,000€: a gap of less than $1000, about 100 times less than the current gap in America. For those who understandably blame shying away from primary care on the debt burden, the question is whether they would be truly satisfied with the salary primary care physicians currently earn in exchange for tuition-free medical school.

Before other medical schools with colossal endowments or fundraising capacity simply race to making attendance tuition-free for all, I would caution the leaders to carefully study the impact that it would have on our society. It is a powerful statement to be able to support so many students’ education, but it would be an even more powerful one to use those funds with more intentionality when targeting the shortage of primary care providers, and aiming to address issues of diversity in medicine.